What is demand response?

What is demand response? Let’s think about it this way. Imagine you have turned up at the airport, e-ticket in hand, only to be told your plane is full.

There are no other flights immediately available, but the airline has a solution: if you can volunteer to miss the flight and wait for a later one you will be compensated – through an upgrade, a voucher, or maybe a free night in a good hotel. At least from one perspective you’re better off.

Though rare in Australia, this is often how air travel works elsewhere. In the US, flights are routinely overbooked. Inconvenienced passengers may grumble, but they also mostly recognise that supply of any good is not infinite. And if they lose out – by choice, hopefully – they win in another way.

A similar idea is behind the growing push for what is known as demand response, or demand management, in electricity.

The thinking goes like this: just as it would make little sense for an airline to put on another flight for a handful of passengers, there is not much economic sense in building another power plant to service a tiny number of consumers at the few times a year when electricity use peaks. What if, instead, consumers were offered an incentive to cut use during extreme circumstances?

Phil Cohn, from the Australian Renewable Energy Agency business development and transactions team, says consumers treat electricity differently to other goods. They expect it to be available at all times. “For any other industry, it seems people accept there are limitations on supply,” he says.

Why there is a problem

Ensuring there were no limitations on supply in the National Electricity Market led to what now seem perverse economic decisions. On extreme summer days, when the temperature across the eastern seaboard climbs beyond 40 degrees and the more than half of Australian homes and businesses with air-conditioners have them buzzing at full bore, we use 46 per cent more electricity than average.

Until recently, we responded to this by building generators that we hardly ever use – mostly natural gas-fired plants that are turned on for as little as 20 hours a year.

It’s an expensive business. The 550MW plant completed near Mortlake, in Victoria’s west, in 2012 cost $640 million but, as with other plants of its type, it gets used only at times of extreme demand when the spot price for wholesale electricity can reach $14,000 per MW hour (the maximum allowed in the National Electricity Market that covers most of the country, though not Western Australia or the Northern Territory). Usually, the wholesale price is a tiny fraction of that – about $100 per MW hour.

It means an unreasonable proportion of wholesale electricity bills goes toward ensuring the lights stay on for that tiny fraction of the year when demand peaks.

The simple idea behind demand response is that rather than pay to increase how much capacity is available we pay to reduce the amount of electricity we use. It’s cheaper and more efficient. There are no guarantees in electricity generation and there have always been black outs, but it should significantly reduce the risk of the sort of event that hit Sydney in February, when the city narrowly avoided the lights going out as the temperature soared and some power plants failed.

A global solution

Several jurisdictions have already headed down this path. Texas last year had 3616MW of demand (more than double the recently retired Hazelwood coal plant in the Latrobe Valley) available to be called on as part of its response reserve service. Other systems covering groups of US states can decrease use by between 3 and 7 per cent of peak demand.

Japan turned to demand response as part of the solution in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and Korea introduced laws in 2014 encouraging its use. The biggest player in the latter market, EnerNOC, last year announced its portfolio was greater than 1000MW, equivalent to one of Korea’s nuclear power plants.

Audrey Zibelman, who recently arrived from New York to run the Australian Energy Market Operator [AEMO], says demand response is an increasingly common approach. “From Texas to Taiwan, demand response has been proven to be a cost-effective way to manage demand at peak times and acts as a contingency to avoid disruptive power outages.”

But demand response is still finding its sea legs, with much of its potential yet to be tapped. The Paris-based International Energy Agency last year described it as a potential game-changer for electricity markets, estimating it could cut use at peak times by 15 per cent.

In Australia, there has traditionally been some resistance, in part due to energy companies that build generation plants having significant sway in the policy debate. The Australian Energy Market Commission [AEMC], which draws up the rules for the electricity and gas markets, was commissioned by federal and state governments five years ago to look at options, but little came from it.

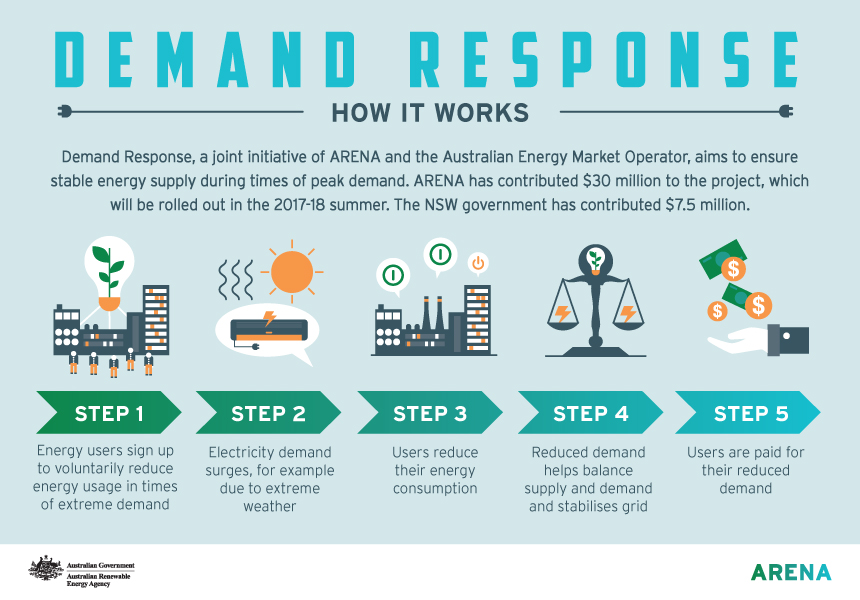

Under a trial program announced in May, ARENA is offering $30 million over three years to support demand response demonstration projects across the national market. Another $7.5 million will be invested by the NSW Government for projects in that state.

The money will be paid to electricity users that agree to be available to cut use when called on by AEMO. It is a significant shift: from just talking to generators about how to fix problems to including energy users as part of the solution.

Early indications suggest the appetite will outstrip what the program can provide. An indicative survey found there could be 700MW of capacity – half a Hazelwood, in operational terms – available to be taken out of the system by the coming summer. By the following summer it could be 2000MW.

Mr Cohn says: “That was giving people a week’s notice and not being particularly scientific, but just in terms of getting a sense of the magnitude of the untapped resources out there that was pretty exciting.”

How will demand response work?

Under the initial program, it is expected that electricity users would be paid up to $12.5 million a year to have 160MW capacity on standby to take offline. The hope is they will never be called on. If they are, the agencies say it will be for no more than 10 times a year, for no more than four hours at a time.

Those who sign up could be large industrial operations – water companies willing to temporarily shut down some pumping, for example. They could be commercial users willing to delay or shift production for a few hours. And they could be energy retailers that would themselves sign up households to be involved.

Those households could sign over control of some appliances, such as pool pumps and air-conditioners, so retailers could turn them off if necessary. Or households may agree to be sent a message asking them to cut use. Those who did would get a discount on the next bill, or a cash bonus.

The payment for the shut down time would be made by AEMO, at a market-set rate and in addition to the $37.5 million already dished out by ARENA and the NSW government.

It may not be as easy to get your head around as a suburb covered in photovoltaic panels, but Mr Cohn says it can be just as effective. “It’s very diverse in the way it’s done – you can’t see an exciting wind farm or solar array – but diversity is the strength,” he says.

This article was originally written by Adam Moreton, Journalist.

LIKE THIS STORY? SIGN UP TO OUR NEWSLETTER

ARENA